C5: The Digestive Journey - Breaking Down & Building Up

Welcome to the pre-lab reading for our exploration of the fascinating world of digestion! Before you step into the lab, it’s crucial to understand the fundamental processes your body uses to transform the food you eat into the energy and building blocks it needs to function. This reading will guide you through the major players and actions in this intricate system.

1. Introduction: What is Digestion?

Digestion is the complex process of breaking down large, often insoluble food molecules into smaller, water-soluble molecules that can be absorbed into the bloodstream and utilized by the body’s cells. This transformation is essential for obtaining nutrients, which provide energy and the raw materials for growth and repair.

Think of it like dismantling a complex Lego structure into its individual bricks so you can use those bricks to build something new.

The digestive system accomplishes this through two main types of actions:

- Mechanical Digestion: The physical breakdown of food into smaller pieces.

- Chemical Digestion: The chemical breakdown of food molecules into their simpler subunits using enzymes.

2. The Players: Organs of the Digestive System

The human digestive system, also known as the gastrointestinal (GI) tract or alimentary canal, is a long, muscular tube extending from the mouth to the anus. It’s aided by several accessory organs that produce or store secretions vital for digestion.

2.1 The Alimentary Canal:

- Mouth (Oral Cavity): The entry point. Here, mechanical digestion begins with chewing (mastication), and chemical digestion of carbohydrates starts with salivary amylase.

- Pharynx & Esophagus: Passageways for food. The pharynx is a y-shaped tube connecting the mouth to the esophagus. The esophagus is a muscular tube that propels food to the stomach via peristalsis (wave-like muscle contractions).

- Stomach: A J-shaped muscular organ that churns food (mechanical digestion) and secretes gastric juices containing hydrochloric acid (HCl) and the enzyme pepsin, which begins protein digestion. The acidic environment (pH around 2-3) also helps kill pathogens.

- Small Intestine: The major site for chemical digestion and nutrient absorption. It’s a long, coiled tube consisting of three parts: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. Enzymes from the pancreas and the small intestine itself complete the breakdown of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.

- Large Intestine (Colon): Absorbs most of the remaining water, electrolytes, and vitamins produced by gut bacteria. It also forms and stores feces.

- Rectum & Anus: The rectum stores feces before they are eliminated from the body through the anus (defecation).

2.2 Accessory Organs:

- Salivary Glands: Secrete saliva, which moistens food and contains salivary amylase.

- Liver: Produces bile, which emulsifies fats (breaks them into smaller droplets), aiding their digestion.

- Gallbladder: Stores and concentrates bile produced by the liver, releasing it into the small intestine when needed.

- Pancreas: Secretes a cocktail of digestive enzymes (amylase, lipase, proteases like trypsin and chymotrypsin) into the small intestine. It also secretes bicarbonate to neutralize stomach acid.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/VWH-EVERGREEN-Your-Digestive-System-in-Pictures-1-TEXT-FINAL-1-1-81ad18233fbb47009cd8da0dad5d4b7f.png) Simplified view of the major organs of the digestive system

Simplified view of the major organs of the digestive system

3. The Processes: Mechanical and Chemical Digestion

As mentioned, digestion involves both physical and chemical changes to food.

3.1 Mechanical Digestion: The Physical Breakdown

Mechanical digestion is the process of physically breaking down food into smaller pieces, increasing its surface area for more efficient chemical digestion.

- Mastication (Chewing): Teeth grind food in the mouth.

- Churning: The stomach’s muscular walls contract to mix food with gastric juices.

- Segmentation: Rhythmic contractions in the small intestine mix chyme (partially digested food) with digestive enzymes.

- Peristalsis: Wave-like muscular contractions that propel food along the GI tract.

Watch this video to see peristalsis in action:

3.2 Chemical Digestion: The Enzymatic Attack

Chemical digestion involves breaking the chemical bonds within large food molecules, transforming them into their smaller, absorbable components with the help of specific digestive enzymes. Enzymes are biological catalysts that speed up biochemical reactions.

Key Characteristics of Digestive Enzymes:

- Specificity: Each enzyme typically acts on only one type of substrate (e.g., amylase digests starch, pepsin digests proteins).

- Optimal Conditions: Enzymes work best within specific temperature and pH ranges. For example, pepsin functions optimally in the acidic environment of the stomach (pH ~2-3), while enzymes in the small intestine prefer a more alkaline environment (pH ~6-7+).

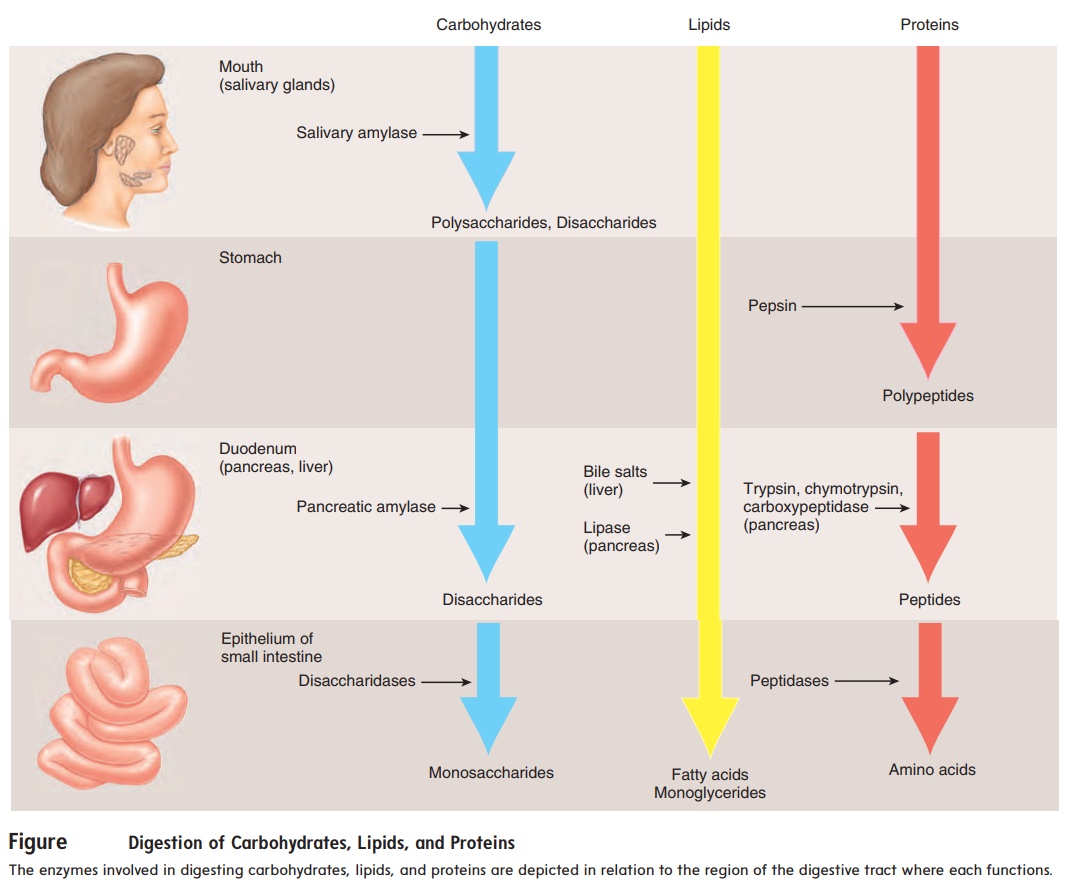

4. Breaking Down the Macromolecules

The major organic macromolecules in our food – carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids (fats) – must be broken down into their simplest forms (monomers) to be absorbed.

4.1 Carbohydrate Digestion:

- Starts in: Mouth with salivary amylase.

- Continues in: Small intestine with pancreatic amylase and enzymes from the small intestine (e.g., maltase, sucrase, lactase).

- Polysaccharides (e.g., starch) are broken down into: Disaccharides (e.g., maltose, sucrose, lactose) and then into monosaccharides (e.g., glucose, fructose, galactose).

- Absorbable units: Monosaccharides (glucose, fructose, galactose).

4.2 Protein Digestion:

- Starts in: Stomach with pepsin (activated from pepsinogen by HCl).

- Continues in: Small intestine with pancreatic proteases (e.g., trypsin, chymotrypsin) and peptidases from the small intestine.

- Proteins are broken down into: Polypeptides, then smaller peptides, and finally into amino acids.

- Absorbable units: Amino acids.

4.3 Lipid (Fat) Digestion:

- Minor digestion in: Mouth (lingual lipase) and stomach (gastric lipase).

- Primarily occurs in: Small intestine.

- Process:

- Bile (from the liver, stored in gallbladder) emulsifies fats, breaking large fat globules into smaller droplets, increasing surface area for enzyme action.

- Pancreatic lipase breaks down triglycerides (the main dietary fats) into fatty acids and monoglycerides.

- Absorbable units: Fatty acids and monoglycerides.

This diagram summarizes the main sites of digestion and absorption:

(Image: Overview of Digestion. Source: brainkart)

(Image: Overview of Digestion. Source: brainkart)

5. What to Expect in the Lab

In the upcoming lab session, we will likely be performing experiments to:

- Investigate the activity of specific digestive enzymes (e.g., amylase on starch, pepsin on protein).

Understanding the principles of digestion and enzyme action discussed here will be crucial for interpreting your experimental results.

6. Conclusion

The digestive system is a marvel of biological engineering, efficiently breaking down diverse food materials into usable nutrients. By understanding the interplay of mechanical and chemical digestion, the roles of different organs, and the specificity of enzymes, you are now better prepared to explore these processes hands-on in the lab.

Make sure you’ve understood the key terms and concepts. This knowledge will form the foundation for our experimental investigations into the fascinating world of digestion!

- Resources

- API

- Sponsorships

- Open Source

- Company

- xOperon.com

- Our team

- Careers

- 2025 xOperon.com

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Report Issues